|

|

Post by Arjan Hut on Apr 22, 2021 6:17:55 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by Arjan Hut on Apr 22, 2021 6:44:51 GMT -5

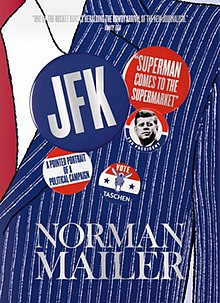

The essay by Mailer:Superman Comes to the SupermarketIn November 1960, Norman Mailer first tried his hand at a genre that would come to define his career. This is Mailer's debut into the world of political journalism, a sprawling classic examining John F. Kennedy. For once let us try to think about a political convention without losing ourselves in housing projects of fact and issue. Politics has its virtues, all too many of them—it would not rank with baseball as a topic of conversation if it did not satisfy a great many things—but one can suspect that its secret appeal is close to nicotine. Smoking cigarettes insulates one from one's life, one does not feel as much, often happily so, and politics quarantines one from history; most of the people who nourish themselves in the political life are in the game not to make history but to be diverted from the history which is being made. If that Democratic Convention which has now receded behind the brow of the summer of 1960 is only half-remembered in the excitements of moving toward the election, it may be exactly the time to consider it again, because the mountain of facts which concealed its features last July has been blown away in the winds of High Television, and the man-in-the-street (that peculiar political term which refers to the quixotic voter who will pull the lever for some reason so salient as: "I had a brown-nose lieutenant once with Nixon's looks," or "that Kennedy must have false teeth"), the not so easily estimated man-in-the-street has forgotten most of what happened and could no more tell you who Kennedy was fighting against than you or I could place a bet on who was leading the American League in batting during the month of June. So to try to talk about what happened is easier now than in the days of the convention, one does not have to put everything in—an act of writing which calls for a bulldozer rather than a pen—one can try to make one's little point and dress it with a ribbon or two of metaphor. All to the good. Because mysteries are irritated by facts, and the 1960 Democratic Convention began as one mystery and ended as another. Most of the people who nourish themselves in the political life are in the game not to make history but to be diverted from the history which is being made.Since mystery is an emotion which is repugnant to a political animal (why else lead a life of bad banquet dinners, cigar smoke, camp chairs, foul breath, and excruciatingly dull jargon if not to avoid the echoes of what is not known), the psychic separation between what was happening on the floor, in the caucus rooms, in the headquarters, and what was happening in parallel to the history of the nation was mystery enough to drown the proceedings in gloom. It was on the one hand a dull convention, one of the less interesting by general agreement, relieved by local bits of color, given two half hours of excitement by two demonstrations for Stevenson, buoyed up by the class of the Kennedy machine, turned by the surprise of Johnson's nomination as vice-president, but, all the same, dull, depressed in its over-all tone, the big fiestas subdued, the gossip flat, no real air of excitement, just moments—or as they say in bullfighting—details. Yet it was also, one could argue—and one may argue this yet—it was also one of the most important conventions in America's history, it could prove conceivably to be the most important. The man it nominated was unlike any politician who had ever run for President in the history of the land, and if elected he would come to power in a year when America was in danger of drifting into a profound decline.

Depression obviously has its several roots: it is the doubtful protection which comes from not recognizing failure, it is the psychic burden of exhaustion, and it is also, and very often, the discipline of the will or the ego which enables one to continue working when one's unadmitted emotion is panic. And panic it was I think which sat as the largest single sentiment in the breast of the collective delegates as they came to convene in Los Angeles. Delegates are not the noblest sons and daughters of the Republic; a man of taste, arrived from Mars, would take one look at a convention floor and leave forever, convinced he had seen one of the drearier squats of Hell. If one still smells the faint living echo of carnival wine, the pepper of a bullfight, the rag, drag, and panoply of a jousting tourney, it is all swallowed and regurgitated by the senses into the fouler cud of a death gas one must rid oneself of—a cigar-smoking, stale-aired, slack-jawed, butt-littered, foul, bleak, hard-working, bureaucratic death gas of language and faces ("Yes, those faces," says the man from Mars: lawyers, judges, ward heelers, mafiosos, Southern goons and grandees, grand old ladies, trade unionists and finks), of pompous words and long pauses which lay like a leaden pain over fever, the fever that one is in, over, or is it that one is just behind history? A legitimate panic for a delegate. America is a nation of experts without roots; we are always creating tacticians who are blind to strategy and strategists who cannot take a step, and when the culture has finished its work the institutions handcuff the infirmity. A delegate is a man who picks a candidate for the largest office in the land, a President who must live with problems whose borders are in ethics, metaphysics, and now ontology; the delegate is prepared for this office of selection by emptying wastebaskets, toting garbage, and saying yes at the right time for twenty years in the small political machine of some small or large town; his reward, one of them anyway, is that he arrives at an invitation to the convention. An expert on local catch-as-catch-can, a small-time, often mediocre practitioner of small-town political judo, he comes to the big city with nine-tenths of his mind made up, he will follow the orders of the boss who brought him. Yet of course it is not altogether so mean as that: his opinion is listened to—the boss will consider what he has to say as one interesting factor among five hundred, and what is most important to the delegate, he has the illusion of partial freedom. He can, unless he is severely honest with himself—and if he is, why sweat out the low levels of a political machine?—he can have the illusion that he has helped to chooses the candidate, he can even worry most sincerely about his choice, flirt with defection from the boss, work out his own small political gains by the road of loyalty or the way of hard bargain. But even if he is there for more than the ride, his vote a certainty in the mind of the political boss, able to be thrown here or switched there as the boss decides, still in some peculiar sense he is reality to the boss, the delegate is the great American public, the bar he owns or the law practice, the piece of the union he represents, or the real-estate office, is a part of the political landscape which the boss uses as his own image of how the votes will go, and if the people will like the candidate. And if the boss is depressed by what he sees, if the candidate does not feel right to him, if he has a dull intimation that the candidate is not his sort (as, let us say, Harry Truman was his sort, or Symington might be his sort, or Lyndon Johnson), then vote for him the boss will if he must; he cannot be caught on the wrong side, but he does not feel the pleasure of a personal choice. Which is the center of the panic. Because if the boss is depressed, the delegate is doubly depressed, and the emotional fact is that Kennedy is not in focus, not in the old political focus, he is not comfortable; in fact it is a mystery to the boss how Kennedy got to where he is, not a mystery in its structures; Kennedy is rolling in money, Kennedy got the votes in primaries, and, most of all, Kennedy has a jewel of a political machine. It is as good as a crack Notre Dame team, all discipline and savvy and go-go-go, sound, drilled, never dull, quick as a knife, full of the salt hipper-dipper, a beautiful machine; the boss could adore it if only a sensible candidate were driving it, a Truman, even a Stevenson, please God a Northern Lyndon Johnson, but it is run by a man who looks young enough to be coach of the Freshman team, and that is not comfortable at all. The boss knows political machines, he know issues, farm parity, Forand health bill, Landrum-Griffin, but this is not all so adequate after all to revolutionaries in Cuba who look like Beatniks, competitions in missiles, Negroes looting whites in the Congo, intricacies of nuclear fallout, and NAACP men one does well to call Sir. It is all out of hand, everything important is off the center, foreign affairs is now the lick of the heat, and senators are candidates instead of governors, a disaster to the old family style of political measure where a political boss knows his governor and knows who his governor knows. So the boss is depressed, profoundly depressed. He comes to this convention resigned to nominating a man he does not understand, or let us say that, so far as he understands the candidate who is to be nominated, he is not happy about the secrets of his appeal, not so far as he divines these secrets; they seem to have too little to do with politics and all too much to do with the private madnesses of the nation which had thousands—or was it hundreds of thousands—of people demonstrating in the long night before Chessman was killed, and a movie star, the greatest, Marlon the Brando out in the night with them. Yes, this candidate for all his record; his good, sound, conventional liberal record has a patina of that other life, the second American life, the long electric night with the fires of neon leading down the highway to the murmur of jazz.

(Read the entire article here: www.esquire.com/news-politics/a3858/superman-supermarket/)

The essay has its own Wikipedia-page (synopsis included): Superman Comes to the Supermarket

|

|

|

|

Post by Arjan Hut on Apr 22, 2021 7:14:56 GMT -5

"From Mexico, Goodpasture had worked on the case of Rudolph Abel, a Soviet agent working in New York City and curiously, living one apartment below famed author, FPCC activist and latter-day CIA apologist Norman Mailer." ( Lisa Pease, James Jesus Angleton and the Kennedy Assassination, Probe, 2000)  Abel (right) about to be exchanged for Francis Gary Powers Abel (right) about to be exchanged for Francis Gary PowersRudolf Ivanovich Abel (Russian: Рудольф Иванович Абель), real name William August Fisher (July 11, 1903 – November 15, 1971), was a Soviet intelligence officer. He adopted his alias when arrested on charges of conspiracy by the FBI in 1957. Fisher was born and raised in Newcastle upon Tyne in the North of England in the United Kingdom to Russian émigré parents. He moved to Russia in the 1920s, and served in the Soviet military before undertaking foreign service as a radio operator in Soviet intelligence in the late 1920s and early 30s. He later served in an instructional role before taking part in intelligence operations against the Germans during World War II. After the war, he began working for the KGB, which sent him to the United States where he worked as part of a spy ring based in New York City. In 1957, the U.S. Federal Court in New York convicted Fisher on three counts of conspiracy as a Soviet spy for his involvement in what became known as the Hollow Nickel Case and sentenced him to 30 years' imprisonment at Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, Georgia. He served just over four years of his sentence before he was exchanged for captured American U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers. Back in the Soviet Union, he lectured on his experiences. He died in 1971 at the age of 68. ( Wikipedia, retrieved 4-22-21) Related:129 Photo showing Oswald at Powers trial |

|

|

|

Post by Arjan Hut on Aug 20, 2021 4:17:28 GMT -5

In April 1963, aided by Thomas Vicente, the FBI broke into FPCC NY offices for a black bag operation. FBI files indicate that NY alone had over 25 covert informers who were being used along with other sources. Tampa had at least 11 informants carrying the TP-T code. The CIA also was all over the FPCC. Two days after the FPCC ad in the NY Times, William K. Harvey, head of the CIA’s Cuban affairs, told FBI counterintelligence chief Sam Papich: “For your information, this Agency has derogatory information on all individuals listed in the attached advertisement.”* Other files confirm that Jane Roman and James Angleton were also monitoring the FPCC. ( Exposing the FPCC, part 1) (*This included Norman Mailer, AH) |

|