|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 19:41:19 GMT -5

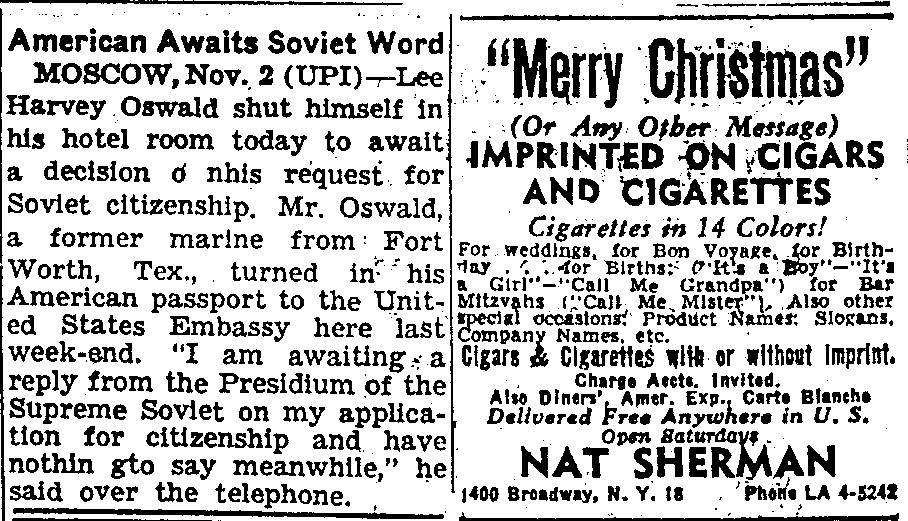

Who Was Nat Sherman?by Herbert Blenner | Posted November 10, 2000 On November 3, 1959, The New York Times published an advertisement containing alien characters next to the report on the defection of Lee Harvey Oswald. The Nat Sherman company sold premium tobacco products and supplies since 1930. This family-owned business in New York City has been passed down through two or three generations. Currently, Nat Sherman Inc. is located at the intersection of 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

During the fifties, Nat Sherman combined business and pleasure. He typically spent the winter months in Cuba where he purchased his tobacco. For the dog days of summer, Nathan N. Sherman had a place in Cold Spring, New York. Possibly, Nat Sherman had a town residence in Jackson Heights, about twenty minutes from Manhattan.

Nat Sherman wrote his own advertisements and did his own photography. This would explain the many advertisements he published with anomalies. Most errors such as unbalanced quotation marks, unbalanced parentheses, a misspelled word or transposition of two lines of text could have been accidental. The key point being no one could show these errors were intentional. Fortunately, Nat Sherman published an advertisement that contained clearly legible characters that are not part of our language. The production of a line of text containing a large superscript comma and a superscript period with an electric typewriter requires the five-step sequence of half-down, comma, change font wheel, period, and half-up. This complicated sequence of steps rules out accidental production. This advertisement was published by The New York Times on November 3, 1959.

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 19:48:54 GMT -5

Anatomy of an Encrypted Communicationby Herbert Blenner | Posted on April 17, 2000 A detailed examination of anomalies in an article on Lee Harvey Oswald and an adjacent advertisement show that Nat Sherman intentionally included the irregularities in his ad.

Part One - The Article

The United Press International article, "American Awaits Soviet Word," originated in Moscow on November 2, 1959 and appeared the next morning in the New York Times. This article on Lee Harvey Oswald contained fifteen lines of text and about seventy words. They published two incorrectly spaced words, on his and nothing to, which appeared as "o nhis" and "nothin gto."

Around 1960 the publication of any United Press International article would start with a written story being sent by teletype-link to subscribing newspapers whose teletype would print a draft quality article and simultaneously punch a paper tape. If the story were selected for publication then the punched tape would be feed into a Justo-writer that produced letter quality print justified to one column width. Next they would cut and paste up the justified article.

Newspapers used mechanical Justo-writers because figuring out where to insert spacers to produced a justified line of text was too complicated for typists. The machine would count character by character the accumulated width of a line until it reached the width of the column. Then the machine would backtrack to the first space while decreasing the accumulated line width. Next the machine would take the difference between the column width and the decreased line width as the padding space. The final algorithm would place an additional space between words until the line width reached the column width. That is right, Justo-writers were mechanical computers.

I should emphasize a Justo-writer inserts padding spaces between words by recognizing the space character as word separators. Where they were no spaces, no additional padding would be added. At most, a Justo-writer would increase the number of spaces between incorrectly spaced words. The incorrectly spaced words, "o nhis" and "nothin gto," came out of the Justo-writer because they were feed in with incorrect spacing.

Suppose United Press International in Moscow transmitted the words "on his" and "nothing to" with correct spacing. If The New York Times received "o nhis" and "nothin gto" then the communications link caused four character recognition errors resulting from sixteen individual bit errors.

Two successive character recognition errors could have caused the first pair of incorrectly spaced words. The New York Times would have received the transmitted bit sequence for lowercase n, 1101110, as the 0100000 bit sequence for a space. Next, they would have received the following transmitted bit sequence, 0100000, for a space as the 1101110 bit sequence for a lowercase n.

Bit sequences are numbers and the transmitter and receiver keeps a tally, known as a checksum, of all numbers sent and received during a communication. Following the message the transmitter sends its checksum. If the checksum calculated by the receiver did not equal the checksum sent by the transmitter then the receiver detected an error. This error detection scheme would work when two errors occur with just one exception.

The second error was the singularly unique error out of 127 possible errors that frustrated the error detection scheme. United Press International sent 1101110 and 0100000 whose partial checksum is 10001110 and The New York Times received 0100000 and 01101110 whose partial checksum is 10001110.

Similar remarks apply to the second pair of incorrectly spaced words. The New York Times would have received the transmitted bit sequence for lowercase g, 1100111, as the 0100000 bit sequence for a space. Next, they would have received the following transmitted bit sequence, 0100000, for a space as the 1100111 bit sequence for a lowercase g. They would have caught the third communication error if the fourth singularly unique communication error did not occur.

Every one of the sixteen individual bit errors affected only data bits. Not once did an error occur on the start or stop bits sent with every bit sequence. The communications link missed sixteen opportunities to flag a framing or overrun error. If the optional parity bit were employed then this test would have failed because each of the four erroneous bit sequences had an even number of bit errors.

Individually each character recognition error would have been an unlikely event. Frustration of the checksum as an error detection scheme by a singularly unique error would have been a rare event. The failure to detect any error in the sixteen individual bit errors and the double frustration of the checksum test is not a tenable explanation of the origin of the two incorrectly spaced words. Either United Press International in Moscow sent two incorrectly spaced words or The New York Times engineered the two incorrectly spaced words.

The explanation that UPI in Moscow sent two incorrectly spaced words ignores the role of Soviet censorship. Censors had a keen interest in Western press reports on the "defectors." They delayed the first article on Robert E. Webster for about three days and held part of the initial report of the "defection" of Lee Harvey Oswald in censorship. Without question, Soviet censors reviewed the second article on Oswald before they permitted UPI to send their story. I doubt the censors approved a story with incorrectly spaced words or someone at UPI risked prosecution for espionage by embedding the incorrect spacing after receiving approval.

The alternate explanation that The New York Times engineered the two incorrectly spaced words avoids the problems caused by Soviet censorship and would explain why the spacing errors got by the proofreaders.

Part Two - The Advertisement

The Nat Sherman advertisement contains an anomaly. In place of the opening quote in "It's a Boy" a large comma and a period appear as superscripts.

However, in our language we print commas and periods as subscripts and use the superscript position for apostrophes and quotation marks. Our keyboards, typewriters, replaceable font wheels, and typesets do not include the comma or the period as superscripts.

Distracted, incompetent or drunk typesetters may only mistakenly set a character belonging to their typeset. Physically the span of any typesetting error is limited to characters in the typeset. I dismiss the possibility of error by a typesetter because two types from alien typesets of two different font sizes would have to have been selected to replace a single type.

I doubt that Nat Sherman produced advertisements by the typeset method. He combined six different styles of text to give his advertisements their distinctive appearance. Elaborate advertisements would have been too complicated to typeset and too expensive to publish six days a week.

Advertisers who published the same ads repeatedly affected a significant cost reduction by using the photographic method. Nat Sherman alternated between two advertisements between October 1959 and December 1959. He published about forty advertisements from two pieces of artwork.

Nineteen advertisements were the same type as the advertisement published on November 3, 1959 but did not contain the anomalous punctuation. The print published on November 3, 1959 was photographically distinct from nineteen other similar advertisements. An examination of the photographic technique will illuminate this discrepancy.

People would use an electric typewriting with a replaceable font wheel to print lines of text of common font and size then cut and paste the individual lines to master artwork. In this manner, they generated advertisements containing various fonts and font sizes. When the artwork was finished, they photographed it. After they retouched the negative to remove any streaks or alignment guidelines, they made non glossy prints for inclusion in the newspapers.

The production of a line of text containing a large superscript comma and a superscript period from an ordinary keyboard requires the five-step sequence of half-down, comma, change font wheel, period, and half-up. If anyone were to assert that the anomaly in the November 3, 1959-Nat Sherman advertisement was an accident then they would incur liability of showing how someone could mistakenly perform five steps in place of one.

The Nat Sherman advertisement published on November 3, 1959 was the product of deliberate photographic manipulation. Amateur photographers had the tools and techniques to superimpose two images on one sheet of photographic paper. They required a photographic enlarger, removable red filter to cover the projection lens, and a red mask to define the size and position the altered section. First they would place the unaltered negative in the enlarger and project the image through the red filter onto non glossy photographic paper. Next, they placed the red mask over the section they wanted to change. They removed the red filter for a couple of seconds to make their first exposure. Then they replaced the original negative by a negative containing a large comma and a period.

They positioned the negative so that the new image fell on the red mask. Finally they would lift the red mask and remove the red filter for a couple of seconds to produce the second exposure. The doubly exposed print would then be processed in the normal manner.

Nat Sherman wrote his own advertisements and had the opportunity and knowledge to do his own photography. His business was walking distance from Willoughby's, a primary source of photographic equipment and darkroom supplies, where they knew Nat as a regular.

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 19:53:31 GMT -5

Comparison of Two Defectors

by Herbert Blenner | Posted October 13, 2000

Robert E. Webster represented a plastics manufacturer at a trade show in Moscow during 1959. He met a woman named Vera and starting dating her. After the show ended, Mr. Webster defected to the Soviet Union.

The New York Times devoted two articles to Webster's defection. When Webster decided to return to the U.S., he merited four articles in The New York Times.

In late October, the article, "American Picks Life in The Soviet" announced the defection of Robert E. Webster. This article contained the error "C.E. Webster, the father said no telephone call had yet been received. He and his wife said: ceived. He and his wife said:" These mangled lines gave the appearance of an editing error after they wrote the story.

The next day, the New York Times published "Wife of Defector Voices Suspicions" (1) that developed the "another woman" theme. Surprisingly, the staid New York Times reported Mr. Webster had seen a lot of Vera but they did not tell us how often he saw her.

In March 1962, the media became aware of the desire of Robert E. Webster to return to the U.S. The New York Times published the article, "American in Russia Seeks Return Here," with two groups of illegible symbols between the words "employe" and "Rand." The first group might have been the word "of."

During May, The New York Times reported Robert E. Webster's pending return in the article, "Man Who Renounced U.S. to Return." (2) Four days later, they reported Webster's return in the article, "Defector to Soviet is Back to 'Undo Wrong' to U.S." (3) Both these articles were error free.

The last article on Robert E. Webster, "Ex-Ohioan is Questioned on Three Years in Soviet" reported his testimony before a Congressional committee. This article contained the error "The hearing took place behind closed doors."

Three out of six articles published by The New York Times on Robert E. Webster contained errors. This 50 percent error rate is atypical for any newspaper and suggests that The New York Times reported more than they printed. Robert E. Webster had a contemporary who defected to the Soviet Union in 1959 and returned to the United States in 1962. This contemporary was Lee Harvey Oswald. The Dallas Morning News, The New York Times, and The Washington Post reported the defection of Lee Harvey Oswald. The Times article, "Ex-Marine Requests Soviet Citizenship", described Oswald's demonstration at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. Most newspapers showed little interest in Oswald's story. The Chicago Daily Tribune, Herald Tribune (New York City), Los Angeles Times, New York Daily News, Times - Picayune (New Orleans), and The Washington Post did not follow up on the initial report of Oswald's defection. Lee Harvey Oswald received special treatment by The New York Times. They published the follow-up article, "American Awaits Soviet Word" (4) with the words, "on his" and "nothing to" printed as "o nis" and "nothin gto." Probably, these errors were pointers to the adjacent Nat Sherman advertisement.(5) This Nat Sherman advertisement contained an anomaly. In place of the opening quote in "It's a Boy" a large comma and a period appear as superscripts. Production of a line of text containing these anomalies required the five-step sequence of half-down, comma, change font wheel, period, and half-up. The complexity of this process rules out accidental production. I conclude Nat Sherman intentionally embedded an encoded message in his advertisement. By contrast on six separate occasions, The New York Times published a Robert E. Webster article and an errorless Nat Sherman advertisement on different pages. Source: The New York TimesOctober 21, 1959, pg. 5, "Wife of Defector Voices Suspicions" May 17, 1962, pg. 12, "Man Who Renounced U.S. to Return" May 21, 1962, pg. 4, "Defector to Soviet is Back to 'Undo Wrong' to U.S." November 3, 1959, pg. 8;7, "American Awaits Soviet Word" November 3, 1959, pg. 8;8, Nat Sherman advertisement

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 19:57:16 GMT -5

Implications of the Encrypted Communicationby Herbert Blenner | Posted May 8, 2000 The appearance of intrigue surrounding the reported defection of Lee Harvey Oswald suggests many possibilities.

Immediate Responses

My first thoughts were that Oswald was an agent and the encrypted communication was a dangle enhancement. My examination of The New York Times articles on the defection of Robert E. Webster allowed the dangle theory. The October 20, 1959-article, article, "American Picks Life In The Soviet," (3) contained the error "C.E. Webster, the father, said no telephone call has yet been received. He and his wife said: ceived. He and his wife said:" I wondered if the editors mangled the lines to give the appearance of last-minute changes.

Naturally, new speculations soon replaced my initial thoughts. Both articles on Webster and Oswald contained errors. No one could prove these errors were intentional. However, the November 3, 1959-article on the defection of Oswald was beside a Nat Sherman advertisement with an irrefutable encrypted message. I speculated that they gave Oswald special treatment because he was a real defector.

After a while, I began to rationalize the encrypted communication was a hoax that someone implanted in the microfilm record of The New York Times after the assassination of President Kennedy. I found this explanation a relief. No longer did I carry the burden of explanation or exploration. I continued with an unrelated line of research for the next two years.

Meditated Responses

I came to realize that the assassination of President Kennedy would have caused every U.S. Government agency who could have had contact with Lee Harvey Oswald to conduct an extensive search of their records. If the encrypted communication was the product of U.S. Intelligence activity, it would have been found and deleted from the microfilm record of The New York Times. The failure of the U.S. Intelligence community to delete the encrypted communication of November 3, 1959 from the record of The New York Times forced me to discount the dangle theory.

Some critics claim members of the U.S. Intelligence community intentionally inserted the encrypted communication into the microfilm record after the assassination of President Kennedy. Their purpose was to manufacture false proof of the independence between the U.S. Intelligence and Oswald. This disinformation argument is more difficult but possible to evaluate.

Background of the encrypted communication

During the ten years preceding November 3, 1959, Nat Sherman published about fifteen erroneous advertisements. His errors included unbalanced quotation marks (4) and unbalanced parentheses. (5) He misspelled words by omitting a letter (6) or transposing two letters. (7) In one advertisement, Nat Sherman transposed two lines of text. (8) Some Nat Sherman advertisements contained misplaced periods. (9) One Nat Sherman advertisement had a slash in place of a space (10) and other advertisements had an illegible letter. (11) I doubt that anyone can prove these errors were intentional.

However, the Nat Sherman advertisement of May 26, 1953 contained intentional anomalies. (12) The closing quotation marks in "It's A Boy" contained symbols of unequal font size and the opening quotation marks in "It's A Girl,"contained three instead of two symbols.

Nat Sherman used a font similar to Times New Roman that had different symbols for open and closed quotation marks. The closed quotation marks resembled two apostrophes, printed side by side and the open quotation marks looked like the close quotation marks turned upside down. Nat Sherman had to manufacture the three-symbol open quotation marks because his open quotation marks contained symbols that differed from the apostrophe. He also needed to produce close quotation marks with the first symbol larger than the second. Nat Sherman deliberately embedded two characters that did not belong to our language in his advertisement. The inclusion of an encrypted message in the Nat Sherman advertisement of November 3, 1959 was not an isolated occurrence. The existence of just one precedent, the encrypted communication in the advertisement of May 26, 1953, is proof of an ongoing clandestine activity probably for the private sector. Nat Sherman embedded elusive messages in his advertisements that escaped detection for four decades. Probably, we would never have detected Nat Sherman's activities if Lee Harvey Oswald did not become the accused assassin of President Kennedy. The association of the November 3, 1959-encrypted communication with an ongoing activity renders the disinformation explanation implausible. U.S. Intelligence would have carefully researched any intentionally planted disinformation. Probably they would have found the adjacency between the erroneous Nat Sherman advertisement of November 28, 1951 (11) and the article, "Slansky Is Seized By Prague As Spy," (13) somewhat disturbing. Alternately they would have been highly embarrassed by the adjacency of the article, "14 Purged Reds Go On Trial In Prague" (14) and the November 21, 1952-Nat Sherman advertisement. (8) The most damaging discovery they would have found was the association between the irrefutable encrypted communication in the Nat Sherman advertisement of May 26, 1953 and the front page article, "Rosenberg Appeal Denied For 3D Time By Supreme Court." (15) There goes the disinformation theory. The encrypted communication of May 26, 1953 weakens the hoax theory of the encrypted communication of November 3, 1959. Similarity between these two irrefutable encrypted communications almost demands that any prankster had foreknowledge of the advertisement from May 26, 1953. The alternate explanation that both encrypted communications were part of the same hoax avoids the problem of foreknowledge but does not explain the necessity of an elaborate prank. In fact the entanglement of the encrypted communication of November 3, 1959 with a previous encrypted communication reduces the veracity of the hoax theory. Motive for the encrypted communicationThe immediate cause of the encrypted communication of November 3, 1959 was the publication by The New York Times of the November 1, 1959-article, "Ex-Marine Requests Soviet Citizenship." (16) This article described Oswald's attempted defection the previous day at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, discussed the aborted defection of Nicholas Pertrulli, the completed defection of Robert Webster and, ended with the statement, "The rest of this dispatch was held in censorship." Nat Sherman revealed the urgency surrounding the defection of Lee Harvey Oswald by producing the encrypted communication of November 3, 1959. He did not produce an advertisement with unbalanced quotation marks or unbalanced parentheses. Nor did Nat Sherman misspell a word or transpose two lines of text. He did not misplace a period, substitute a slash for a space, or include an illegible letter. Nat Sherman did not use any of these methods to produce a debatable message. Instead, Nat Sherman manufactured proof of his ongoing clandestine activities. He did this intentionally for some purpose that lies outside the scope of the November 3, 1959-encrypted communication. Source: The New York Times1. November 3, 1959, page 8, column 7, "American Awaits Soviet Word" 2. November 3, 1959, page 8, column 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 3. October 20, 1959, page 3, "Webster's Parents Shocked" 4. June 1, 1951, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 4. August 4, 1953, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 4. August 20, 1952, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 5. July 31, 1959, page 2, Nat Sherman advertisement 6. October 31, 1951, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 7. July 31, 1959, page 2, Nat Sherman advertisement 8. November 21, 1952, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement 9. June 19, 1953, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 9. August 18, 1953, page 9, Nat Sherman advertisement 9. June 23, 1956, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement 10. November 28, 1952, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement 11. November 21, 1951, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 12. May 26, 1953, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement 13. November 28, 1951, page 8, "Slansky Is Seized By Prague As Spy" 14. November 21, 1952, page 6, "14 Purged Reds Go On Trial In Prague" 15. May 26, 1953, page 1, "Rosenberg Appeal Denied For 3D Time By Supreme Court" 16. November 1, 1959, page 3, "Ex-Marine Requests Soviet Citizenship"

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 20:02:59 GMT -5

Infamous Spy Trials of the Early Fiftiesby Herbert Blenner | Posted June 9, 2000 Nat Sherman had a special interest in the Rosenberg case of 1950-1953 and the Prague trial of 1951-1952. We find many coincidences of erroneous Nat Sherman advertisements with articles on these spy trials. More significantly, Nat Sherman published an encrypted message on the same day as the doomsday article on the Rosenbergs. In the initial phase of the Rosenberg case we find the coincidence of two Nat Sherman advertisements with articles on the Rosenberg case. On July 18, 1950, the article, "Fourth American Held As Atom Spy," (1) reported the arrest of Julius Rosenberg and appeared on the same page as a Nat Sherman advertisement. (2) The July 20, 1950-article "More Arrests Seen In Atomic Spy Case" (3) appeared on page eighteen and a Nat Sherman advertisement was published on page six. (4) If Nat Sherman advertised daily then a coincidence of his advertisement with any article on the Rosenberg case could be discounted. At the opposite extreme, if Nat Sherman advertisements only appeared on the days when they published an article on the Rosenberg case then the coincidence would be difficult to dismiss. Nat Sherman was an infrequent and irregular advertiser in The New York Times during the early fifties. So the dates on which Nat Sherman advertised before and after a coincidence between an advertisement and an article on the Rosenberg case is of interest. The two Nat Sherman advertisements published on the same day as the initial articles on the Rosenberg case were preceded by the advertisement of July 13, 1950 and followed by the advertisement of July 24, 1950. During the fall of 1952, doubts arose that the Courts were going to uphold the death sentences imposed upon the Rosenbergs. An international movement to curb abuses in spy trials arose in Europe in 1951 and reached the U.S. during 1952. These events were echoed by The New York Times and Nat Sherman advertisements. On November 8, 1952, the article "New Trial Petition Filed For Rosenbergs" (5) was published on page six near a Nat Sherman advertisement. (6) This Nat Sherman advertisement of November 8, 1952 was preceded by the October 25, 1952 advertisement and followed by the November 14, 1952-advertisement. The article, "716 Stage Rally for Atom Spies at Ossining; Demonstrators Are Kept Away From Prison," (7) was published on December 22, 1952 along with a Nat Sherman advertisement.(8) Nat Sherman advertisement of December 22, 1952 was preceded by his December 19, 1952 advertisement and followed by his January 19, 1953. By the spring of 1953, any doubt that the Courts would uphold the death sentence imposed in the Rosenberg case vanished. In the final month before the execution of the Rosenbergs four Nat Sherman advertisements were published on the same day as articles on the Rosenberg case. On May 19, 1953, the article "High Court Delays Rosenberg Ruling" (9) was published on page nineteen and a flawless Nat Sherman advertisement (10) appeared on page six. The following week Nat Sherman published the first of his two known advertisements containing irrefutable encrypted messages. This advertisement of May 26, 1953 was published on page 8 along with the front page article, "Rosenberg Appeal Denied for 3d Time by Supreme Court." The page one article, "High Court Denies A Rosenberg Stay; New Plea Up Today" (11) from June 16, 1953 was published with a page eight Nat Sherman advertisement that contained a broken vertical border. (12) On June 19, 1953, a Nat Sherman advertisement in which a large dot appears under the last letter in "CIGARETTES" (13) was published on page eight with the four articles, "Spies 'Overjoyed' By News Of Delay," (14) "Many Abroad Ask Mercy For Spies," (15) "High Court Rules On Spy Case Today," (16) and "5 To Study Impeachment." (17) The dates on which Nat Sherman published advertisements that surround those advertisements published during the last month of the Rosenberg case are May 8, 1953, May 19, 1953, May 26, 1953, June 1, 1953, June 16, 1953, June 19, 1953, and June 23, 1953. The Prague TrialIn the initial phase of the Slansky prosecution we find the coincidence of two Nat Sherman advertisements with articles on Slansky case. On November 28, 1951, the article "Slansky Is Seized By Prague As Spy," (18) reported the arrest of Rudolf Slansky and appeared on the same page as Nat Sherman advertisement. (19) The first letter in the word "two" in this advertisement was illegible. The November 30, 1951-article, "More Arrests Seen For Czech Officials," (20) appeared on page 8 and a Nat Sherman advertisement was published on page six. (21) The dates of Nat Sherman advertisements that surround his November 28, 1951 and November 30, 1951 advertisements are November 26, 1951 and December 3, 1951. The May 3, 1952-article "61 Red Leaders Reported Ousted" (22) reported former Foreign Minster Vladmir Clementis and party Secretary Rudolf Slansky were charged with working for the West. This page six article appeared with an error-free Nat Sherman advertisement. (23) This May 3, 1952-Nat Sherman advertisement was bounded by his April 26, 1952 and May 10, 1952 advertisements. Two articles, "14 Purged Reds Go On Trial In Prague" (24) and "Kremlin's Hand Seen in Czech Purge Trial", (25) were published on page six on November 21, 1952 along with a Nat Sherman advertisement that had two lines of text transposed (26). On November 28, 1952, a page six-Nat Sherman advertisement (27) contained the error "We carry every famous/brand of cigars in our . . ." and the article "11 Czechs Must Die; 3 Others Get Life on Treason" (28) appeared on page one and was continued on page four. The Nat Sherman advertisement of November 14, 1952 preceded his November 21, 1952 advertisement and his December 12, 1952 advertisement followed his November 28, 1952 advertisement. Source: The New York TimesJuly 18, 1950, page 8, "Fourth American Held as Atom Spy" July 18, 1950, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement July 20, 1950, page 18, "More Arrests Seen in Atomic Spy Case" July 20, 1950, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement November 8, 1952, page 6, "New Trial Petition Filed for Rosenbergs" November 8, 1952, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement December 22, 1952, page 10, "716 Stage Rally for Atom Spies at Ossining; Demonstrators Are Kept Away From Prison" December 22, 1952, Page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement May 19, 1953, page 19, "High Court Delays Rosenberg Ruling" May 19, 1953, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement June 16, 1953, page 1, "High Court Denies a Rosenberg Stay; New Plea Up Today" June 16, 1953, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement June 19, 1953, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement June 19, 1953, page 8, "Spies 'Overjoyed' by News of Delay" June 19, 1953, page 8, "Many Abroad Ask Mercy for Spies" June 19, 1953, page 8, "High Court Rules on Spy Case Today" June 19, 1953, page 8, "5 to Study Impeachment" November 28, 1951, page 8, "Slansky is Seized by Prague as Spy" November 28, 1951, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement November 30, 1951, page 8, "More Arrests Seen for Czech Officials" November 30, 1951, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement May 3, 1952, page 6, "61 Red Leaders Reported Ousted" May 3, 1952, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement November 21, 1952, page 6, "14 Purged Reds go on Trial in Prague" November 21, 1952, page 6, "Kremlin's Hand Seen in Czech Purge Trial" November 21, 1952, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement November 28, 1952, page 6, Nat Sherman advertisement November 28, 1952, page 1, "11 Czechs Must Die; 3 Others Get Life on Treason"

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 20:09:14 GMT -5

Rosenberg Case and Defection of Lee Harvey Oswaldby Herbert Blenner | Posted on May 3, 2000 Aline Mosby interviewed Lee Oswald in Moscow probably on November 13, 1959. Oswald said: "I'm a Marxist, . . . I became interested about the age of 15. From an ideological viewpoint. An old lady handed me a pamphlet about saving the Rosenbergs. . . I looked at that paper and I still remember it for some reason, I don't know why."(1)

Lee Oswald was in New York City between September 1952 and June 1953 while Emanuel H. Bloch unsuccessfully fought the conviction of the Rosenbergs in the courts. Superficially, it seems plausible that the bitter controversy surrounding the Rosenberg case affected a teenage Lee Oswald. This explanation could explain why Oswald abruptly brought up the subject of the Rosenbergs during his interview and ended the discussion with the remark, "I don't know why." Perhaps Oswald knew "something special" about the Rosenberg case and was not inclined to tell Aline Mosby.

A review of the Rosenberg Case as reported by The New York Times shows they published three Nat Sherman-advertisements on the same page as an article on the Rosenberg case. The first Nat Sherman advertisement coincided with the report on the arrest of Julius Rosenberg. (2) The second advertisement appeared on the same page as the article on the filing of a petition for a new trial (3) and the Times published the third advertisement on the day that the Rosenbergs were executed. (4 - 7)

Of course we could dismiss these coincidences as accidental. However, the explanation that The New York Times published a Nat Sherman advertisement beside the article "American Awaits Soviet Word" (8) by coincidence fails to explain the deliberate photographic manipulation of this Nat Sherman advertisement. (9)

A large superscript comma and superscript period replace the opening quotation marks on "It's a Boy." However, our keyboards and typesets contain commas and periods as subscripts. Further the font size of the superscript comma is larger than other characters in "It's a Boy." These considerations exclude accidental inclusion of the large superscript comma and superscript period in this Nat Sherman advertisement.

Between October and December of 1959, Nat Sherman published twenty advertisements with the same design as his ad of November 3, 1959. Nineteen of these had normal punctuation and only the advertisement that appeared next to the article on the defection of Lee Harvey Oswald contained the large superscript comma and superscript period.

During the ten years preceding November 3, 1959, Nat Sherman published about fifteen erroneous advertisements. His errors included unbalanced quotation marks and unbalanced parentheses. He misspelled words by omitting a letter or transposing two letters. In one advertisement, Nat Sherman transposed two lines of text. I doubt that anyone can prove these errors were intentional.

However, the Nat Sherman advertisement of May 26, 1953 contained intentional anomalies. (10)

The closing quotation marks in "It's A Boy" contained symbols of unequal font size and the opening quotation marks in "It's A Girl," contained three instead of two symbols.

Nat Sherman used a font that had different symbols for open and closed quotation marks. The symbol of the closed quotation marks resembled two apostrophes, printed side by side and the open quotation marks looked like the close quotation marks turned upside down. These anomalous symbols are not part of our language. He could not find these symbols on a typewriter keyboard or a Daisy wheel. Nat Sherman had to manufacture three-symbol open quotation marks because the ordinary open quotation marks contained symbols that differed from the apostrophe. He also needed to produce close quotation marks with unequal symbol size. Nat Sherman deliberately manipulated this advertisement to include an encrypted message.

One story published by The New York Times on May 26, 1953, commands special attention. They reported on page one that the Supreme Court denied the Rosenberg appeal for the third time. (11) This refusal by the Supreme Court effectively sealed the fate of the Rosenbergs. Julius and Ethel were doomed and Nat Sherman used this occasion to introduce his new product. Mr. Sherman was very pleased with his "BLACK CIGARETTES."

The inclusion of an encrypted message in the Nat Sherman advertisement of November 3, 1959 was not an isolated occurrence. The existence of just one precedent, the encrypted message in the advertisement of May 26, 1953, is proof of an ongoing clandestine activity. Nat Sherman embedded elusive messages in his advertisements that escaped detection for three decades. Probably, we would never have detected Nat Sherman's activities if Lee Harvey Oswald did not become the accused assassin of President Kennedy.

The immediate cause of the encrypted communication of November 3, 1959 was the publication by The New York Times of the November 1, 1959-article, "Ex-Marine Requests Soviet Citizenship." (12) This article described Oswald's attempted defection the previous day at the U.S. embassy, discussed the aborted defection of Nicholas Pertrulli, the completed defection of Robert Webster and, ended with the statement, "The rest of this dispatch was held in censorship."

On November 2, 1959, Nat Sherman produced an advertisement containing a large superscript comma and a superscript period in place of an opening quotation mark. If whim or contingency inspired Nat Sherman, he could have saved many steps by masking out an opening or closing quotation mark. Alternately Nat Sherman could have introduced a spelling error by masking a letter. These changes would not have required a second negative or a second exposure. Nat Sherman did not take these shortcuts because his purpose was to produce an advertisement that would link Lee Harvey Oswald with the events surrounding the advertisement of May 26, 1953.

The encrypted communication of November 3, 1959 betrays the urgency felt by Nat Sherman following the defection of Lee Harvey Oswald. Nat Sherman risked exposure of his ongoing clandestine operation by coupling the article, "American Awaits Soviet Word" with two incorrectly spaced words to his advertisement that contained an encrypted message. He had no illusions about the dangers wrought by the defection of Lee Harvey Oswald. Nat Sherman knew what Oswald might have learned about the Rosenberg case while a student in New York City.

References

Warren Commission Report, Chapter VII, "Interest in Marxism", paragraph 2

July 18, 1950, page 8, "Fourth American Held as Atom Spy"

November 8, 1952, page 6, "New Trial Petition Filed for Rosenbergs"

June 19, 1953, page 8, "Spies 'Overjoyed' by News of Delay"

June 19, 1953, page 8, "Many Abroad Ask Mercy for Spies"

June 19, 1953, page 8, "High Court Rules on Spy Case Today"

June 19, 1953, page 8, "5 to Study Impeachment"

November 3, 1959, page 8, column 7, "American Awaits Soviet Word"

November 3, 1959, page 8, column 8, Nat Sherman advertisement

May 26, 1953, page 8, Nat Sherman advertisement

May 26, 1953, page 1, "Rosenberg Appeal Denied for 3d Time by Supreme Court"

November 1, 1959, page 3, "Ex-Marine Requests Soviet Citizenship"

Unless otherwise indicated the above references refer to The New York Times

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 20:15:42 GMT -5

Ghost of the Prague Trialby Herbert Blenner | Posted May 28, 2000 The overturn of the convictions in the Prague trial of 1952 by the Czechoslovak Government sent a clear signal to the Kennedy administration that a relaxation of tensions in the cold war was possible. Chance for a Cold War ThawBetween the spring and summer of 1963, the Czechoslovak Government undertook a review of the political trials of 1949-1955. The New York Times focused upon the Prague trial of 1952 and reported on the efforts of the Czechoslovak Government to undo their conviction of Rudolf Slansky and Vladimir Clementis. The first article, "Shake-Up Reported in Slovak Communist Party," appeared on April 26, 1963 and reported suggestions that Rudolf Slansky maybe cleared of crimes against the state. The second column of this article, under the banner "Ferment of Anti-Stalinism . . . ," contained the error: "The same posthumous rehabilitation may also be in view for Vladimir Clementis, a Slovak Communist executed with Slansky .an seven others." On August 9, 1963, the page three article, "Czech Court 'Restores', Slansky, Hanged in 1952,to Legal Status," stated that Rudolf Slansky has been juridically rehabilitated and the Czechoslovak Supreme Court has found that Dr. Alexei Cepicka, former Deputy Premier and Defense Minister, and Ladislav Koprivas, former State Security Minister, had violated legality in a criminal manner. This article contained the error: "Among the others, all sentenced to death by hanging, were Mr. Slansk and Vladimir Clementis, a former Czech Foreign Minister." The next article "Slansky and 8 Others Absolved by Czech Court" appeared on page twenty of The New York Times on August 22, 1963. This article contained the error: "The Czechoslovak news agency CTK. said the Czech Supreme Court had absolved Mr. Slansky and eight other former Communist officials, including former Foreign Minister Vlado Clementis, on all points of the indictment presented against them in Nov. 1952." On the following day, August 23, 1963, the articles "Slansky Verdict is Left in Doubt" and "2 Former Aides Sentenced" appeared on the same page as a Nat Sherman' advertisement. The latter article reported that two-former Deputy Interior Ministers, Col. Antonin Prchal and Col. Karel Kostal, were sentenced to prison for "fabricating untrue accusations" and "violating legality in the course of investigations" in the political trials of the early fifties. The full significance of these articles on the reversal of the convictions of Slansky and Clementis and the prosecution of those who acted illegally was revealed during the Prague spring of 1968. What Might Have Happened?In the summer of 1963, President Kennedy directed his brother and Attorney General, Robert Kennedy, to quietly undertake a review of the Rosenberg case. While the inner circle of the Kennedy administration debated how far they should go in undoing the Rosenberg conviction, members of the intelligence community fought vigorously to block any undoing of the Rosenberg convictions. Robert Kennedy was the principal advocate of a vigorous prosecution of those who had acted criminally. John Kennedy was more restrained and leaned toward an exposure of the illegalities and a finding of wrongful deaths in the Rosenberg case. John Kennedy listened to the arguments of the CIA, FBI, and ONI that reopening the Rosenberg case would have dire consequences but was more strongly influenced by the failure of the intelligence community to provide an explanation of their position. In September of 1963, John Kennedy made the decision to follow Robert Kennedy's advice. In September 1963 rumors of the planned assassination of John Kennedy were planted in Chicago, Miami, and New Orleans. The FBI, through its network of informers, was quick to pick up these rumors and recognized the signature of a CIA operation. The FBI was faced with a paralyzing dilemma; it knew that the only group with sufficient knowledge of operations to threaten to have the blame for the assassination of John Kennedy placed on the CIA was its own secret group of illegal operators consisting of mainly former agents of the FBI and the ONI. J. Edgar Hoover, the master of blackmail, did not dare move against those illegal operators who for decades did the dirty work for the FBI. These illegal operators entrapped and rehearsed the witnesses whose testimony put the leadership of the Communist Party in prison, and affected the infiltration of organized labor by organized crime; first to drive out the leftist influence and then to attack the labor movement in general. Hoover knew these illegal operators had learned their lessons well but had no loyalty to the FBI and would use their knowledge of illegal activities to protect their own interests. The master was held hostage by his own students. The CIA was caught between a rock and a hard place. The illegal operators poured salt into an open wound by using selected members of the Cuban-American communities in Miami and New Orleans, with close ties to the illegal Domestic Operations Section of Central Intelligence, to implant the rumors of the pending assassination of John Kennedy. In 1961, following a review of the Bay of Pigs operation and upon recommendation of Robert Kennedy, John Kennedy fired leading members of the CIA for using the Domestic Operations Section in violation of their charter. Both the FBI and CIA did not intervene to advert the pending assassination. Neither organization could explain their position to the chief prosecutorial officer of the United States without embarrassing and endangering themselves. In most cases this silence would be taken as assent to the assassination. However, there is a special circumstance to be taken in account; individuals of the FBI and the CIA are protected by the self-incrimination clause of the fifth amendment. The Prague SpringIn the months before the assassination of Robert Kennedy, during the spring of 1968, we find, after a five-year lull, interest in the Prague trials of the early fifties. The images most of us were given of the Prague spring as a time of relaxation and plurality was a partial truth. In reality, the Prague spring of 1968 was a period of intense struggle when previously repressed elements of Czechoslovak society, gained political power, and began to oppress their opponents. During April of 1968, The New York Times reported two deaths of government officials who were linked to past purges. Both reports contained typographical errors. The page three article of April 3, 1968, "Inquiry on Jan Masaryk's Death . . . ," contained the error: "The question to which Mr. Sivitak demanded an an- ally have a budget for 1958-1969. swer was this:" This article appeared below the picture of the body of Dr. Jozef Brestansky hanging from a tree. Dr. Brestansky was the deputy president of the Czechoslovak Supreme Court who was drafting a rehabilitation law for those unjustly imprisoned during the fifties and was recently accused of having passed harsh sentences in a case based on "artificially construed" charges. The April 20, 1968-article "Czech Found Dead; Linked to Masaryk" was published on page six with an error-free Nat Sherman' advertisement. This article reported on the death of Major Bedrich Pokorny, a former intelligence officer, who investigated the death of Jan Masaryk. In describing the circumstances of the 1948 death of Jan Masaryk, the article erroneously stated: "He was found dead in the courtyard of the Foreign Ministry shortly after the Communist takepover in that year." Between the end of April and early May of 1968, two articles appeared on the Prague trial of 1952. The first article appeared with an erroneous Nat Sherman' advertisement and the second article contained a pair of unbalanced quotes. The April 29, 1968-page six article "Czech Charges Slansky Purge in 1952 Was Ordered by Stalin" was published adjacent to a Nat Sherman' advertisement in which part of the words "business" and "gifts" were missing. The previous advertisement of April 27, 1968 and the following advertisement of April 30, 1968 were printed in full. The article of May 8, 1968, "Soviet Tied to Czech Purges" from page ten contained two successive paragraphs with opening quotes and no closing quotes. The implicit danger in openly discussing the role of the KGB in using forged evidence to press for the prosecution of Rudolf Slansky became explicit by the end of May. An unidentified member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia gave a European reporter an extensive interview on the Soviet role in the Prague trial of 1952. This member asserted that the secret evidence the KGB that linked the defendants to the CIA was withheld from the Czech courts and that the KGB pressured officials of the Czechoslovak Government to falsify evidence (probably the forged letter) in order to secure convictions at the Prague trial. The member then abruptly lamented as his voice cracked. "We could not believe that anyone could be so deceitful, that anyone would stoop to such treachery." After a brief pause the member explained: "A western intelligence agency had manufactured the evidence against Slansky and Clementis that was picked up by the KGB." This interview provided one more interesting detail. The manufactured evidence was picked up by the KGB at the temporary headquarters of the United Nations on Long Island. Reaction to the publication of this interview was atypical. There were no instant denials of the allegation that a counter-intelligence operation that resulted in numerous deaths was conducted on the premises of the United Nations. Nor were there any complaints from either the United Nations or any individual member on the charged charter violation. The most curious sign was silence of the western press who had for fifteen years blamed the KGB for the injustice of the Prague trial.

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 20:17:38 GMT -5

Bon oVyageby Herbert Blenner | Posted November 23, 2005 Nat Sherman was a tobacconist who intentionally included alien characters in his advertisements. Between 1949 and 1968, the New York Times published more than four hundred advertisements for Nat Sherman and just two contained these intentional anomalies. They published the first advertisement in 1953 and the second in 1959.

On May 26, 1953, the New York Times published a Nat Sherman advertisement, which included two alien characters. He replaced the closing quotation marks in "It's A Boy" by symbols of unequal font size and substituted a three-symbol character for the opening quotation marks in "It's A Girl."

This advertisement used a font that had different symbols for opening and closing quotation marks. The closing quotation marks resembled two apostrophes and the opening quotation marks resembled the closing quotation marks turned upside down. Since the apostrophe differs from the symbols of the opening quotation marks, Nat Sherman had to consciously manufacture his three-symbol opening quotation marks. He also needed to produce closing quotation marks with the first symbol larger than the second. These considerations show that Nat Sherman deliberately embedded in his advertisement two characters that did not belong to our language.

On November 3, 1959, the New York Times published the second Nat Sherman-advertisement containing intentional anomalies. In this ad, he replaced the opening quotation marks of "It's a Boy" by a large superscript comma and superscript period. Since our keyboards or typesets do not contain these characters, Nat Sherman had to consciously manufacture them. The striking similarities between the intentional alterations of May 26, 1953 and November 3, 1959 provide strong evidence of a relationship between these advertisements.

The New York Times published the advertisement of November 3, 1959 beside an article, which described a telephonic conversation between a reporter in Moscow and Lee Harvey Oswald. This article contained two misspelled words. They published on his as "o nis" and nothing to as "nothin gto."

Within two weeks, Lee Harvey Oswald spoke to another reporter. He told Aline Mosby of the impact that the Rosenberg case had on him as a teenager in New York City.

At the time of the interview, observers suggested that Lee Harvey Oswald raised the issue of the Rosenberg case as a ploy to have the press publish inadvertently an esoteric message. Further, the front-page article on the third and final denial by the Supreme Court to review the conviction of the Rosenbergs, which accompanied the Nat Sherman advertisement of May 26, 1953 underscores the Rosenberg case as an underlying motivation.

Without doubt, Nat Sherman had a special interest in the Rosenberg case. Although he was an infrequent advertiser during the early fifties, his advertisements appeared next to articles on the arrest, prosecution and pending execution of Julius Rosenberg.

On July 11, 1959, Nat Sherman introduced a new format for his ads. He alternated headlines reading "Merry Christmas" and "Congratulations." In the second advertisement of this series, he added "For Bon oVyage" under the "Congratulations" headline. The publication date of this ad was July 31, 1959.

In less than three months from the publication of this curious advertisement, Lee Harvey Oswald used an obscure and expeditious route to enter the Soviet Union. This route later became known as the Browder express.

Earl Browder was a former General Secretary of the Communist Party of the United States who was expelled in 1946 for following policies adopted by the party in 1956 and fully implemented by 1959. On November 26, 1959, the New York Times published a Nat Sherman-advertisement headlined "Merry Christmas" beneath an article entitled, "U.S. drops charge against Browder." Within months of this concurrence Earl Browder and associates were publicly operating Union Tours. This organization specialized in tours of the Soviet Union and used the Helsinki connection.

The United States Government indicted Earl Browder for fraudulently abetting the entry of his Soviet-born wife into the United States. The government charged that Browder knowingly made false statements when he asserted his wife never belonged to a communist party. Curiously, the New York Times published the continuation of their October 1, 1952-story on the indictment of Earl Browder and his wife next to a Nat Sherman-advertisement.

The summer of 1959 was a busy season for Lee Harvey Oswald. A fellow marine, Henry J. Roussel, Jr., arranged a date for Oswald with his aunt, Rosaleen Quinn, a stewardess who took leave from Pan America Airlines to study the Russian language

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 12, 2019 20:20:32 GMT -5

Affidavit of Henry J. Roussel, Jr.

I, Henry J. Roussel, Jr., 2172 Elissalde Street, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, being first duly sworn, depose and say:

That while in the United States Marine Corps I served for approximately three or four months with Lee Harvey Oswald in MACS-9 in Santa Ana, California.

On one occasion I arranged a date for Oswald with my aunt, Rosaleen Quinn, an airline stewardess who, because she was interested in working for the American Embassy in Russia, had taken a leave from her job in order to study Russian. I arranged the date because I knew of Oswald's study of the Russian language. I also arranged a date for my aunt with Lieutenant John E. Donovan. I am under the impression that prior to studying Russian, Oswald had studied German.

I recall no serious political remarks on the part of Oswald. On occasion, however, Oswald, when addressing other Marines, would refer to them as "Comrade." It seemed to me and, as far as I know, to my fellow Marines--that Oswald used this term in fun. At times some of us responded by calling him "Comrade." Oswald also enjoyed listening to recordings of Russian songs.

My recollection of Oswald is to the effect that he was personally quite neat, and that he stayed to himself. Oswald complained about orders that he was given, but no more than did the average Marine. I regarded Oswald as quite intelligent, in view of the fact that he had taught himself two foreign languages. I do not recall Oswald's having any dates other than the one which I arranged for him with my aunt.

I do not remember Oswald's getting into any fights. I have no recollection concerning Oswald's reading habits, religious beliefs, or trips off the post. I do not remember his reading a Russian newspaper, and do not recall his having any nicknames. (I was nicknamed "Beezer.") I do not remember Oswalds having his name written in Russian on his jacket, and have no recollection of any visitors received by Oswald.

Signed this 25th day of May, 1964, at Baton Rouge, La.

(S) Henry J. Roussel, Jr.,

HENRY J. ROUSSEL, Jr. [/p]

Rosaleen Quinn, CE 2015

On December 13, 1963, Miss ROSALEEN QUINN 214 East 84th Street, Apartment 2D, New York City, New York advised SA ROGER H. LEE that she has been a stewardess for Pan American Airlines for the past seven years. She stated that during the summer of 1959 she took a leave of absence from Pan American and accompanied her nephew, HENRY ROUSELL, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to Santa Ana, California. She remained in Santa Ana for approximately one week and resided in a private boarding house. She stated that during the period that she was in Santa Ana she would occasionally visit her nephew, who was in the Marine Corps and stationed in Santa Ana. She remarked that her nephew had arranged two dates for her and the first one of these dates was with LEE HARVEY OSWALD, who was an acquaintance of her nephew's and also a member of the Marine Corps. She advised that her nephew had told her that OSWALD was studying the Russian language and since she had taken a Berlitz course in this language her nephew felt that it would give both of an opportunity to practice speaking the language. She stated that one the night of the date with subject her nephew brought subject to the boarding house where she was residing, introduced subject to her and then both subject and she had dinner and attended a movie.

Miss QUINN recalled that OSWALD was a quiet individual and that it was difficult to converse with him. She commented that she thought OSWALD spoke Russian well for someone who had not attended a formal course in the language. She stated that she could not recall any statement made by OSWALD which indicated that he was dissatisfied with the United States Government or the United States Marine Corps. She stated that in her opinion the evening date with subject did not prove to be a very interesting one and in fact she could not recall whether OSWALD accompanied her back to her boarding house or whether she returned alone. Miss QUINN stated that only other date she had while visiting in Santa Ana was with one Lieutenant DONOVAN, described as OSWALDS Company Commander. She concluded by stating that she has never seen nor heard from OSWALD since the above-described meeting and was unable to furnish any additional information regarding him.

|

|