|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Jan 15, 2019 13:03:22 GMT -5

Punching Holesby Herbert Blenner | Posted November 7, 2007 Commander Humes placed indispensable forensic evidence into the official record. He described the bullet holes of entry as ovals, enumerated the lengths of both axes, reported orientations of the longer axes referenced to the vertical column and specified locations of each hole relative to anatomic features. This forensic information was sufficient to test the compatibility of the medical with the ballistic, eyewitness and the motion picture evidence.

A circular or elliptical hole shows entry by a bullet with a negligible yaw angle. Under these conditions the circular displacement area of the bullet punches a cylindrical wound track beneath the surface. When the direction of a bullet with proper alignment is perpendicular to the struck surface, the hole is circular. More commonly, the trajectory of the bullet makes an angle, known as incidence, with the perpendicular to the surface. Although the bullet still punches a cylindrical wound track, the surface hole is a special type of oval known as an ellipse. Two mutually perpendicular axes characterize an ellipse. These axes, known as the minor and the major, divide the ellipse into two symmetrical portions. For a rigid material, plane geometry proves that the length of the minor axis divided by the length of the major axis equals the cosine of the incidence angle. This relationship enables a forensic analyst to place the trajectory of the bullet on the surface of a cone whose axis is perpendicular to the struck surface and apex coincides with the point of entry. Analytic geometry proves that the major axis lies in the same plane as the striking velocity of the bullet and the length of the minor axis equals the diameter of the bullet. The former result completes the description of the striking angles of the bullet and limits number of trajectories to two. The latter result enables an analyst who knows the diameter of the bullet to adapt the simple analysis of rigid materials to deformable materials, such as tissue or bone.

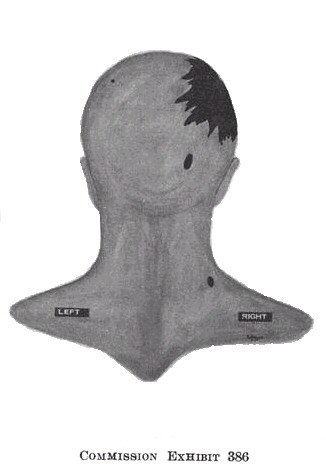

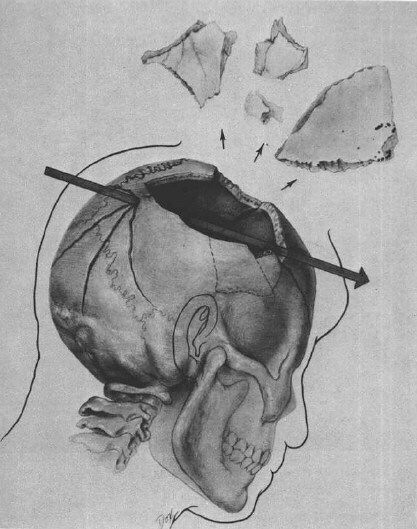

Figure 1 - Bullet holes of entrance

James J. Humes did not quantify the orientation angles of the major axes of the bullet holes. Instead he verbally described the major axis of the hole in the back as roughly parallel to the vertical column. So Commission Exhibit 386, CE 386, has increased importance. It shows that the major axis of the bullet hole in the head made a 18-degree clockwise angle with the direction of the vertical column. For the hole in the back, the major axis made an angle of -15 degree with the vertical column. The purpose of using positive angles for clockwise rotations is to be consistent with the unconventional practice of the Forensic Pathology Panel to reference directions to an imaginary clock. The angular orientation of the major axis gives the azimuthal component of the striking angles of the bullet. This information confines the bullet to two possible trajectories. One trajectory has a positive incidence angle and the other has a negative incidence angle.

When prosectors do not dissect a wound track, forensic analysts choose from several techniques to resolve ambiguity of the algebraic sign. If the abrasion is oval, then they select the trajectory, which makes an acute angle with the more prominent portion of the abrasion. When the incidence angle is sufficiently large to show undermining, then they choose the trajectory that makes an obtuse angle to the undermined portion of the wound. A third method selects the trajectory in the direction of the shallower to the deeper portion of the surface hole. Regrettably, the prosectors did not provide the details to resolve the ambiguous sign.

James J. Humes described the bullet hole in President Kennedy's back as oval with a major axis of 7 mm and a minor axis of 4 mm. He explained that a tangential strike by the bullet elongated the wound and attributed the length of the minor axis being less than the diameter of the 6.5 mm bullet to elastic recoil of the skin. This latter observation shows that James J. Humes gave the dimensions of the bullet hole, which he called a wound. This information is sufficient to calculate the incidence angle of the bullet if oval accurately described the shape.

Distance along the wound track accounts for the elongation of the major axis. Specifically the square of this distance equals ( 7 mm ) 2 - ( 4 mm ) 2 or 33 mm 2. When elastic relaxation and swell of tissues have negligible effect upon this length, the square of the unreduced length of the major axis, b, minus the square of the unreduced length of the minor axis, a, equals 33 mm 2, where a is the 6.5 mm diameter of the bullet. Hence b 2 - ( 6.5 mm ) 2 = 33 mm 2. Solving this equation yields b = 8.7 mm. The cosine of the incidence angle equals the length of the unreduced minor axis divided by the length of the unreduced major axis. Thus, the angle of incidence is ±42 degree.

The reported dimensions of the bullet hole are rounded to one significant figure. So the actual length of the major axis should be taken as 7 ±0.5 mm. Likewise the real length of the minor axis is 4 ±0.5 mm. These uncertain dimensions produce a span for the magnitude of incidence angle. Calculations yield 41 ±5 degree.

When the trajectory has negligible curvature, the angle between the geographic horizontal and the initial direction of the wound track is the declination angle of the bullet. By definition incidence is the angle between the direction of the perpendicular to the entry site and the initial direction of the wound track. So the angle between the direction of the horizontal and the perpendicular equals the incidence angle minus the declination angle. This difference of the two angles also equals the angle between the geographic vertical and the direction of a tangent to the surface at the entry site. For a declination angle of 20 degree and an incidence angle of +42 degree, the tangent to the surface makes an angle of -22 degree with the vertical. This case represents a 22-degree recline angle. Alternately the negative incidence angle, yields a difference of 20 degree minus -42 degree or 62 degree as the angle between the vertical and a leaning surface. These results are amenable to geometric proof.

An analytic solution of this problem in three dimensions changes the angles of recline and lean by less than two degrees and justifies the two-dimensional simplification of this particular situation.

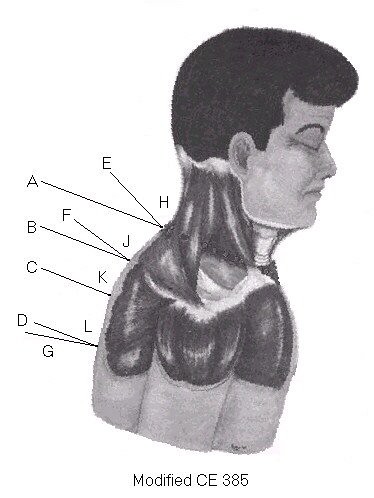

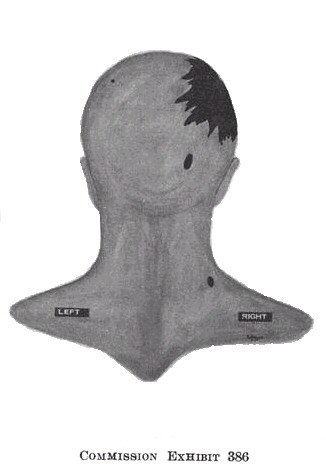

Figure 2 - Testing lower entry sites

A modification of CE 385 shows that lowering the entry site of the back wound decreases the incidence angle. Point H is the original entry site on CE 385 and AH represents the original trajectory with a 12-degree clockwise rotation of the entire graphic to give the trajectory an apparent 20-degree declination angle. This rotation explicitly shows the Warren Commission explanation of the bullet holes in the back and neck of President Kennedy.

Constructing the perpendicular, EH, at point H enables measuring the angle of incidence, AHE, as 27 degree. Under these conditions a 6.5-mm bullet with negligible yaw angle punches an elliptical surface hole with an unreduced minor axis of 6.5 mm and an unreduced major axis of 6.5 mm / cos 27 degree or 7.3 mm. Distance along the wound track accounts for elongation of the major axis. The square of this unreduced distance equals (7.3 mm ) 2 - ( 6.5 mm ) 2 or 11 mm 2. Since the effects of elastic relaxation and swell of tissue upon the contributory distance along the wound track are small, the unreduced distance is approximately equal to the reduced distance. So the reduced length of the major axis, b', and the reduced length of the minor axis, a', satisfy the relationship, b' 2 - a' 2 ~ 11 mm 2. Taking a' = 4 mm gives b' ~ 5.2 mm. This elongation of the major axis by 30% is a mere 40% of the 75% elongation reported by James J. Humes.

Repeating the above procedure at lower points of entry J, K and L show that the incidence angle decreases at point L, becomes zero at point K and increases at the lowest test point L. Since distances between these trial points are negligible compared with the height of the shooter above the back, the respective trajectories BJ, CK and DL are essentially parallel.

Curvature of the back changes the directions of the respective perpendiculars, FJ, CK and GL. The resultant angles of incidence, BJF = 16 degree, CKC = 0 degree and DLG = -11 degree yield 4.4 mm, 4.0 mm and 4.2 mm as the approximate reduced lengths of the major axes. These results show the irreconcilable conflict between the autopsy description of a 7 mm by 4 mm oval bullet hole in the back of President Kennedy and the Warren Commission explanation of the back wound.

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Jan 16, 2019 14:22:57 GMT -5

Punching Holes - Part Two

by Herbert Blenner | Posted November 7, 2007

The Warren Commission had firm foundations for their explanation of the shooting. Motion picture films of the motorcade were especially valuable in establishing the locations and angular orientations of the victims when shot. Finding an abandoned rifle scientifically linked to the fragments recovered from the limousine and a whole bullet in the former vicinity of Governor Connally placed the shooter at the southeast corner on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository. In one sense, this evidence rendered superfluous forensic analysis of the back wound on President Kennedy. The known locations of shooter and victim disclosed the trajectory angles of the hit. So obtaining the anatomic location of the back wound was sufficient to find the orientation angles at the point of impact. This knowledge enabled reverse engineering of the bullet hole. The failure of the prosectors to report a bullet hole in the back comparable with the hole required by the photographic and ballistic evidence motives a careful study of the back wound discussion by the Forensic Pathology Panel.

Source: HSCA, Vol VII p. 84

(245) The Panel examined photographs of the upper right back with the body on its left side; these included 8 inch by 10 inch black and white negatives and prints Nos. 11 and 12 and 4 inch by 5 inch positive color transparencies and prints Nos. 38 and 39. (All photographs and X-rays were examined with and without the aid of a 10X magnifying lens.) Stereoscopic visualization of paired photographs Nos. 38 and 39 revealed a slight change in the position of the camera between the two exposures. Essentially the photographs consist of a view of the right upper posterior thorax (back), with the camera in a position such that it would be approximately horizontal to the body if the body were erect, or at right angles to the skin surface and parallel to a sagittal plane of the body. Within each photograph is a centimeter ruler which overlies the midline of the back, extending approximately 2.5 centimeters above the upper wound margin and 2 centimeters below the lower wound margin, with its edge approximately 2.5 centimeters medial to the wound margin. The ruler is in the plane of focus of the wound, enabling reasonably accurate measurement of the wound, which is oval, with one end of the long axis between 2 o'clock and 3 o'clock and the opposite end between 8 o'clock and 9 o'clock. The maximum wound diameter, determined by interpolation from the photos, is 0.9 by 0.9 centimeter. The midpoint is estimated to be 13.5 centimeters below the right mastoid process, with the head and neck, as positioned within the photograph, 6 centimeters below the most prominent neck crease and 5 centimeters below the upper shoulder margin. (See fig. 4, a drawing of this wound, and fig. 5, a close-up photograph of it.)

(246) There is a sharply outlined area of red-brown to black around the wound in which there is dried, superficial denudation of the skin, representing a typical abrasion collar resulting from the bullet's scraping the margins of the skin at the moment of penetration. This is characteristic of gunshot wounds of entrance and not typical of exit wounds. This abrasion extends around the entire circumference, but is most prominent between 1 o'clock and 7 o'clock about the defect (with the head at 12 o'clock). In addition, there are several small linear, superficial lacerations or tears of the skin extending radically from the margins of the wound at 10 o'clock, 12 o'clock and 1 o'clock. These measure 0.1, 0.2 and 0.1 centimeter respectively. Photographically enhanced prints of photographs Nos. 38 and 39 reveal much more sharply contrasted color determination and, to some degree, more sharply outlined detail of the abrasion collar described above.

(247) Several members of the panel believe, based on an examination of these enhancements, that when the body is repositioned in the anatomic position (not the position at the moment of shooting) the direction of the missile in the body on initial penetration was slightly upward, inasmuch as the lower margin of the skin is abraded in an upward direction. Furthermore, the wound beneath the skin appears to be tunneled from below upward.

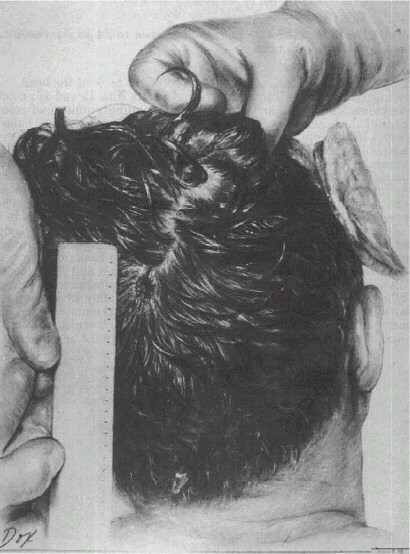

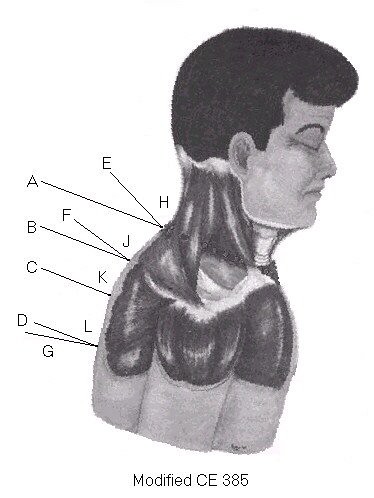

Figure 3 - Dox drawing of the back wound

The Forensic Pathology Panel orientated an imaginary clock with twelve at the head as a directional reference to discuss features seen on the actual photographs. These pictures were the sources for the Dox drawing of the back wound. They described an oval wound with one end of its long axis at 75 degree and the opposite end at 255 degree. The panel placed the more prominent hemisphere of the abrasion between 30 and 210 degree. They noted superficial lacerations at -60, 0 and 30 degree. Further several members recognized that the lower margin was abraded in an upward direction and the wound beneath the skin appeared tunneled from below upward. These observations are mutually inconsistent with scientific analysis of a bullet wound.

A striking bullet induces two stresses in the skin. Obviously the direct contact between the bullet and skin causes the primary stress. The magnitude of this primary stress depends on the distance from the penetrating bullet. When the bullet has a negligible yaw angle, contours of equal stress are circular. For a tangential entry the intersections of these contours with the inclined surface of the skin are ellipses whose axes have the same directions as the axes of the bullet hole. So the primary stress alone yields an elliptical abrasion whose axes align with the axes of the elliptical hole. The secondary stress arises from the attachment of surrounding tissues to those directly impacted and moved by the bullet. This attachment is stiffest where the direction of the penetrating bullet makes the most acute angle with the surface of the skin and least stiff where the angle is most obtuse. So when tissues near the bullet hole have comparable elasticities, the secondary stress widens the portion of the abrasion nearest the most acute angle between the direction of the penetrating bullet and the surface of the skin. This widening effect produces an oval abrasion and its symmetry axis remains coincident with the major axis of the bullet hole.

Assuming that a bullet caused the photographed back wound then the direction of the symmetry axis of the oval abrasion from the more to less prominent portion coincides with the direction of the tangential velocity, Vt, of the striking bullet. For an infinitesimal interval of time, dt, the entering bullet moved a distance ds = Vt dt, which made a 255-degree angle with the vertical on the imaginary clock. This displacement had a slope of 0.97 unit leftward at 9 o'clock for 0.26 unit downward at 6 o'clock. Using the insert of the photographic enlargement of the abrasion enables measurement of the length of the shorter axis divided by the length of the symmetry axis. The quotient of 0.7 agrees with the 7 mm by 10 mm dimensions reported by the Clark Panel. So the incidence angle was approximately the inverse cosine of 0.7 or about 45 degree. This result enables estimating the normal component, Vn, of the velocity of the bullet as the tangential component, Vt, divided by the tangent of the incidence angle. Therefore the normal and the tangential velocities had nearly equal speeds. The three-dimensional picture of the trajectory becomes 0.68 unit leftward, 0.18 unit downward and 0.71 unit directly into the victim. In other words the abrasion shown on photographs of the back wound depicts a bullet on a collision course with the spine.

Figure 4 - Undermining of tissues

Tunneling beneath the skin occurs with every tangential entry and becomes increasingly pronounced with increasing incidence angle. Reading "Undermining of tissues" from left to right shows three tangential entries with incidence angles of 20, 40 and 60 degree. The lightly shaded triangular regions immediately to the left of the wound tracks represent cross sections of undermined tissues. The undermining is most pronounced along the major axis of the bullet hole, becomes less pronounced along directions between the major and minor axes and vanishes at all directions bounded by the minor axis and the portion of the major axis that made an acute angle with the trajectory of the bullet.

An impinging bullet stretches tissue immediately before punching a hole. When the impingement is tangential, the stress in the stretched tissue is largest where the direction of the strain has the smallest radius of curvature. So tears and lacerations congregate around the major axis of the bullet hole where the direction of the striking bullet makes the most obtuse angle with the surface of the skin.

The reported tears and lacerations spanned an arc of 90 degree and were centered around -10 or 350 degree. Without doubt these features were misaligned with both ends of the symmetry axis of the oval abrasion at 75 and 255 degree. However, the tears and lacerations aligned with the superior end of the major axis of the bullet hole at -15 degree as shown on CE 386. These results show that two objects applied forces with substantially different directions upon the back and produced a composite wound. One object produced the hole and margins while the second object caused the oval abrasion. In other words, the Forensic Pathology Panel described photographs of an altered wound.

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Jan 16, 2019 14:31:32 GMT -5

Punching Holes - Part Three

by Herbert Blenner | Posted November 7, 2007

The discussion by the Forensic Pathology Panel on the relationships between an abrasion collar, entrance perforation, bullet trajectory, striking angle and undermining of tissues shows evasion of the issues raised by their descriptions of the back wound based upon the autopsy photographs.

Source: HSCA, Vol VII p. 164

(424) The characteristics of the abrasion collar surrounding the entrance perforation reflect the direction of the bullet at the instant of impact with the skin and the angle of the trajectory prior to contact with the skin, as well as the shape of the missile itself. If the trajectory is perpendicular to the surface of the skin, the hole is usually round and the abrasion collar correspondingly symmetrical around it. (See fig. 45, a picture of an abrasion collar when the missile was perpendicular to the target.) If the angle of the trajectory of the missile to the skin surface is other than perpendicular, the abrasion collar may be asymmetrical, that is, more prominent on the surface with the most acute angle between the skin and the bullet, and less apparent on the opposite surface, where there may be undermining of the tissues. (See fig. 46 showing an abrasion collar produced by a missile striking at an acute area.)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A round abrasion collar surrounding a round entrance perforation shows that the trajectory of the properly aligned bullet was perpendicular to the skin. This definitive statement flows from a forensic analysis that starts with the characteristics of the wound. When the abrasion collar is oval or elliptical it surrounds an elliptical entrance perforation and shows that the trajectory of the bullet was not perpendicular to the surface of the skin. Since an elliptical abrasion collar has two axes of symmetry, it lacks a prominent portion. However, an oval abrasion collar with one symmetry axis has an asymmetry and a more prominent portion. So an oval abrasion collar always has the more prominent portion nearer the side of the wound with the most acute angle and undermining on the opposite side. In reality the Forensic Pathology Panel evaded the particulars of Kennedy's back wound by discussing general contingencies of wounding and in their next paragraph they had the audacity to misrepresent the elliptical wound in Governor Connally's back as virtually rectangular.

Source: HSCA, Vol VII p. 166

(425) If a missile strikes an intervening target, its normal yaw may be exaggerated, or it may begin to tumble. The entry wound in subsequent target might reflect this distortion in trajectory by anything from a very slight asymmetry to an ovoid or virtually rectangular entry wound. The latter would be the case if the missile were to strike sideways and is somewhat similar to what was described in some of the initial medical reports on the wound in the posterior thorax of Governor Connally. (See fig. 47, a drawing showing yawing or tumbling.) Such a subsequent entry wound might show no wipe residue in the skin because of the missile's prior passage through skin and tissue. Some small fragments of the metal from the missile's surface might break off as the missile strikes, however, and adhere to the margins of the defects in either the clothing or skin.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In perhaps the most outrageous obstruction of understanding published by the House Select Committee on Assassinations, the Forensic Pathology Panel presented a graphic entitled, "Figure 46. - Drawing of a typical entry wound, displaying an asymmetrical abrasion collar from a distant rifle shot with a trajectory at an acute angle to the skin surface." Their graphic combined a wildly rotating bullet entering a target at normal incidence with an oval abrasion surrounding an elliptical hole. The panel complemented their contradictions of the foundations of forensic analysis in their following graphic labeled, "Figure 47. - Drawing of an entry wound caused by a tumbling or yawing missile." This graphic showed a bullet with negligible yaw entering a target with a considerable incidence angle and an oval abrasion surrounding a rectangular hole with rounded corners.

The Forensic Pathology Panel did not initiate this obstruction of understanding. Instead they continued and expanded the obstruction practiced by the Warren Commission. Both groups sought to attribute elongation of a wound to entry by a bullet with a considerable yaw angle. Their common purpose was to dispute the relationship between a tangential entry by a bullet and the elongation of an elliptical hole as expressed by James J. Humes in his testimony before the Warren Commission.

Source: Warren Commission, Vol II, page 357

Mr. McCLOY - Was the bullet moving in a direct line or had it begun to tumble?

Commander HUMES - To tumble? That is a difficult question to answer. I have the opinion, however, that it was more likely moving in a direct line. You will note that the wound in the posterior portion of the occiput on Exhibit 388 is somewhat longer than the other missile wound which we have not yet discussed in the low neck. We believe that rather than due to a tumbling effect, this is explainable on the fact that this missile struck the skin and skull at a more tangential angle than did the other missile, and, therefore, produced a more elongated defect, sir.

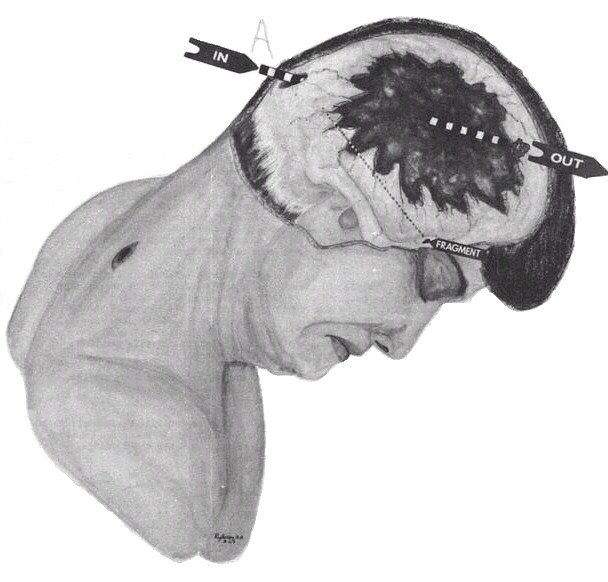

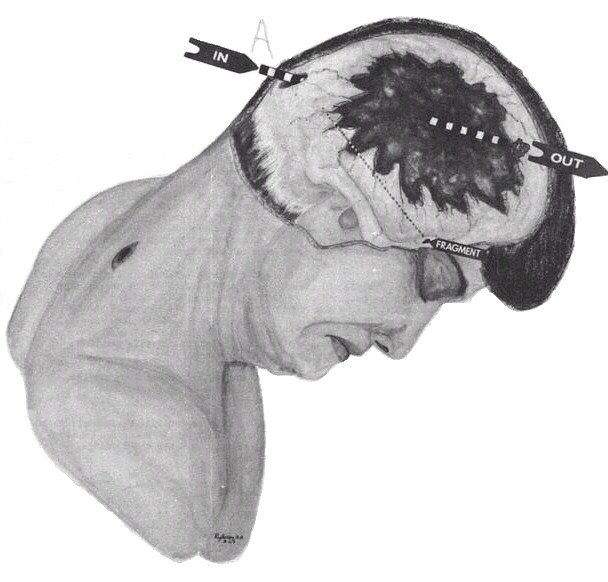

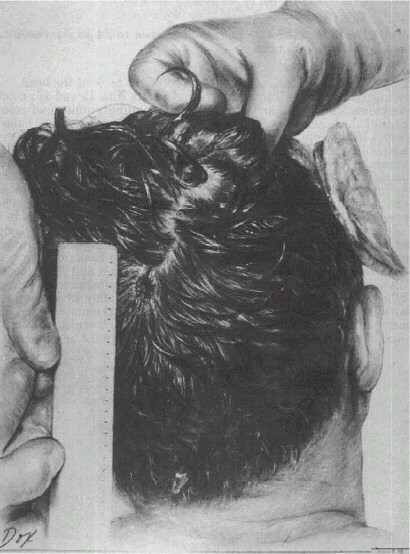

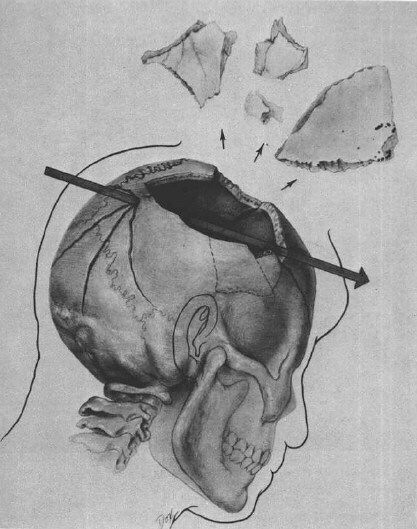

Figure 5 - Commission Exhibit 388

James J. Humes stated that the reduced length of the major axis of the bullet hole of entry in the scalp was 15 mm and the reduced length of the minor axis was 6 mm. So the square of the reduced distance along the wound track equals ( 15 mm ) 2 - ( 6 mm ) 2 or 189 mm 2. The square of the unreduced length of the major axis minus the square of the diameter of the bullet was approximately 189 mm 2. In terms of the unreduced length of the major axis, b, the previous statement yields the equation, b 2 - ( 6.5 mm ) 2 = 189 mm 2. The solution gives b = 15.2 mm and the incidence angle becomes the inverse cosine ( 6.5 mm / 15.2 mm ) or 64.5 degree.

Placing the eyelet of a protractor over the entry hole at point A and aligning the reference line to perpendicularly cross the surface of the head enables reading the incidence angle as 33 degree. The unreduced length of the major axis, b, equals 6.5 mm / cos ( 33 ) or 7.75 mm. Hence the square of the distance along the wound track, which contributes toward the elongation of the major axis is ( 7.75 mm ) 2 - ( 6.5 mm ) 2 or 17.8 mm. 2

When neither elastic relaxation nor swell of tissue change this distance along the wound track, the difference between the square of the reduced length of the major axis, b', and the square of the reduced length of the minor axis, a' equals the square of this invariant length. Symbolically b' 2 - a' 2 = 17.8 mm 2. Taking a' = 6 mm yields b' = 7.34 mm.

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Jan 16, 2019 17:39:24 GMT -5

The line segment NP represents the perpendicular to the entry hole at point P. The trajectory of the bullet symbolized by QP makes an incidence angle of -65 degree with the perpendicular. This geometric construction ensures consistency between the trajectory of the bullet and the dimensions of the elliptical hole. A mental extension of the trajectory shows an exit in the rear portion of the large defect.

Now the forensic analyst is free to rotate the entire graphic to impart the known declination and lateral angles to the trajectory of the bullet. For a shot from the Texas School Book Depository the 15-degree declination angle places the plane of the face 10 degree from horizontal. This alignment allows any rotation about the hips and lean of the head relative to the torso that correctly orientates the head.

The authorities used the shell method to handle the irreconcilable problem caused by the striking angles of the head shot. They said that the scalp entry wound was here then drew the skull entry elsewhere.

Source: HSCA, Vol VII p. 103

(295) The panel examined photographs of the back of the head, including Black and white negatives and prints Nos. 15 and 16; color transparencies Nos. 42 and 43; and correspondingly numbered color prints of the back of the head. These were studied with both the naked eye and 10X magnification. The photographs again all appear to have been taken from approximately the same position, and stereoscopic visualization of the two 4 by 5 inch color transparencies enables three-dimensional perception. In the center of the photographs is a vertical centimeter ruler, which, by stereoscopic visualization, is demonstrated to be slightly closer to the camera than the adjacent skin surface. The upper portion of the ruler, which is in sharpest focus, is adjacent to a slightly oval scalp defect located in the "cowlick" area of the scalp just above or superior to a line drawn between the superior or upper margins of the area. (See fig. 13, a drawing of the back of the President's head.) This defect is partially covered by hair and dried blood. This wound is located considerably above the occipital protuberance, slightly to the right of the midline, and approximately 13 centimeters above the most prominent neck crease. It has a maximum vertical diameter in the photograph of approximately 1.5 to 2 centimeters, and a maximum transverse diameter of approximately 0.9 centimeter.

(296) Accurate reconstruction of the exact dimensions of the wound is difficult because the ruler and wound are in different planes of focus. The long axis of the wound more closely approximates a vertical angle than that depicted within the "Autopsy Descriptive Sheet." (See fig. 6.) The inferior margin of this wound, from 3 to 10 o'clock, is surrounded by a crescent-shaped reddish-black area of denudation, again presenting the appearance of an abrasion collar, resulting from the rubbing of the skin by the bullet at the time of penetration. From 12 to 3 o'clock, there is a suggestion of undermining, that is, tunneling of the tissue between the skin surface and the skull. Three small linear lacerations or tears of the skin, measuring less than 0.2 centimeter, in length, extend radially from the margins of the defect at 11 o'clock, 12 o'clock, and 3 o'clock. (See fig. 14, a close-up photograph of this wound.)

The shape of the defect, excepting a tear near its uppermost perimeter is elliptical and shows a tangential entry by a bullet with a negligible yaw angle. Since the vertical diameter of the abrasion is approximately twice the transverse diameter, these measurements show that the direction of the entering bullet was closer to a tangent than to the perpendicular to the skull. Using 12 o'clock as the zero degree reference places the inferior margin of the wound between 90 and 300 degree. This margin has a mean direction of 195 degree and agrees with the approximate 15 to 195 degree orientation of the long axis of the abrasion. Although the direction of this long axis differs substantially from the axis shown on the "Autopsy Descriptive Sheet" its agreement with the 18-degree angle shown on CE 386 is remarkable.

The suggested undermining beneath the skin between 0 and 90 degree has a mean direction of 45 degree. These observations imply a 30-degree misalignment between the major axis of the bullet hole and the symmetry axis of the abrasion. However, the panel identified undermining by a subjective viewing of photographs. So an error in the angular extent of the undermining is excusable. The tears and lacerations at -30 degree, 0 degree and 90 degree have a mean angle of 20 degree, which aligns with the major axis of the bullet hole at 18 degree.

The Forensic Pathology Panel presented their explanations on the head wounds in JFK Exhibit F-66. They placed the entry site four inches above the hole attributed to a bullet by the prosectors. This relocation enabled the panel to reduce the objectionable 55-degree lean angle shown on CE 388 by 30 degree and show an orientation consistent with the motion picture and eyewitness evidence. The cost of this revision was denial of plane geometry that proves the relationship between the axes of an elliptical hole and the incidence angle of the striking bullet.

Exhibit F-66 shows a bullet striking the rear of the head at a small angle of incidence. The projection of this angle along the line of sight is comparable with its projection in the plane of view. Under these conditions, the major axis of the bullet hole and symmetry axis of the abrasion would make an approximate 45-degree angle on the imaginary clock. However, the smallness of the incidence angle would yield a slightly elliptical hole and abrasion. Clearly these results differ from the 6 mm by 15 mm hole and the 9 mm by 15-20 mm abrasion.

The panel ignored the considerable incidence angle between the outward perpendicular to the skull at the exit site and the trajectory of the bullet. This oversight enabled the panel to present JFK Exhibit F-61 as an explanation of the semicircular beveling of the outer table of the skull at the exit site.

Beveling begins just before a missile exits a tissue unsupported by another substance of comparable or greater yield strength. When the missile reaches a critical distance from the far surface of the tissue, the layer of undamaged tissue becomes too thin to constrain the stress surrounding the transiting missile. At this instant a highly localized bursting of tissue begins at the surface. As the missile moves closer to the surface, the areas of unconstrained stress and bursting at the surface grow larger. Two angles influence the shape of the beveling at the surface. The yaw angle determines the shape of contours of equal stress surrounding the transiting missile. These contours are circular only if the missile has a circular cross section and a negligible yaw angle. When the yaw angle is more six degrees, the contours of equal stress surrounding an undeformed bullet or fragment have parallel sides whose lengths are comparable with the curved ends. For a larger yaw angle, this shape resembles a long rectangle with rounded corners. A considerable incidence angle alters the shape of the contours of equal stress at the bursting surface. Circular contours surrounding a transiting bullet with a negligible yaw angle become elliptical at the surface. Alternately a contour resembling a long rectangle with rounded corners projects upon the bursting surface as an elongated parallelogram with rounded corners. So the semicircular or perhaps an elliptical bevel, hailed as evidence of exit by a bullet, is in reality an impeachment of the trajectory that intersects the inner table of the skull at a large angle of incidence.

In fairness, I acknowledge that the Forensic Pathology Panel was caught between a rock and a hard place. They were given descriptions of the bullet holes of entry that infer a shooting scenario in conflict with the motion picture evidence and eyewitness testimony that had bullets striking an upright Kennedy. In particular the written reports and testimonies of the prosectors support the following scenario.

The first shot missed and alerted President Kennedy to an assassination attempt. He ducked but was struck in the back by a bullet with an approximate 45-degree angle of incidence. The bullet traveled up the neck, possibly inflicted minor damage upon the first thoracic vertebra, entered the cranial cavity from below, passed behind the right eye and exited the front right side of the head at a moderate incidence angle. This bullet produced the elliptical arc described as the semicircular bevel. Another and not necessarily a later bullet hit the rear of the head with an incidence angle of approximately 65 degree and exited to the right and rear of the vertex. The proximity of these exit wounds allowed the later bullet to produce and knock out skull fragments as secondary missiles.

The photographic evidence from Bethesda offered the Forensic Pathology Panel a more unpleasant alternative of calling the back wound altered. However, this was not what the House Select Committee on Assassinations wanted to hear.

Source: HSCA testimony of Dr. Michael Baden, Vol I p. 192

Mr. KLEIN. And the panel found an abrasion collar on the wound of the President's back of the kind you have shown us in these drawings?

Dr. BADEN. Yes, sir. This represents a diagram, a blowup of the actual entrance perforation of the skin showing an abrasion collar. The abrasion collar is wider toward 3 o'clock than toward 9 o'clock, which would indicate a directionality from right to left and toward the middle part of the body, which was the impression of the doctors on reviewing the photographs initially at the Archives.

Mr. KLEIN. Mr. Chairman, at this time, I would ask that the shirt, jacket, and tie, marked JFK F-25, F-26, and F-27, be received as committee exhibits.

Mr. DODD. Without objection.

[The above-referred-to exhibits, JFK F-25, F-26, and F-27, were received as committee exhibits and photographs made for the record.]

Under the circumstances, Dr. Michael Baden acting as spokesperson for the Forensic Pathology Panel did the proper thing. The panel protected their members by clearly disclosing evidence of an altered back wound and allowed the reader to reach their own conclusions.

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 5, 2019 19:04:43 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 5, 2019 19:04:54 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by Herbert Blenner on Feb 5, 2019 19:05:13 GMT -5

|

|